The Bauhaus, simply put, was a German school of art and design that opened in 1919 and closed in 1933. It was also very much more than that. It was the most influential and famous design school that has ever existed. It defined an epoch. It became the pre-eminent emblem of modern architecture and design. The name has become an adjective as well as a noun – Bauhaus style, Bauhaus look. And now it is coming up for the centenary of its founding, which shows both that what was called the “modern movement” is now part of history and that its influence is very much still around us.

It is nowadays usually clear what the word “Bauhaus” means – design stripped down to its essentials, the rational and elegant use of modern materials and industrial techniques, clarity, simplicity, cool minimalism. The device on which I am writing this and the one on which you might be reading it follow these principles. So (with greater or lesser degrees of bastardisation) do buildings without number around the world, countless domestic objects, road signs, the lettering on a tube of toothpaste or the design of a car. The Bauhaus brand is consistent, coherent and universal. Its best-known creations, the tubular steel chairs of Mart Stam and Marcel Breuer or the steel-and-glass building built to house the school, reinforce its image.

Yet the reality was considerably more chaotic and diverse, especially in its early years. It was founded in Weimar by the architect Walter Gropius, by merging the city’s Saxon Grand Ducal Art School and its Academy of Fine Art, with the aim of unifying crafts, art and architecture. Its spirit owed much to Victorian English visionary William Morris. The new institution was irrational as much as rational, mystical as much as practical and medieval as much as modern. It was a ferment of creative types pushing, pulling, fighting and collaborating.

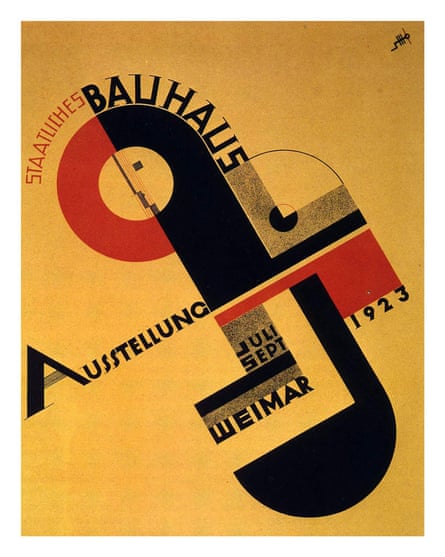

The school’s founding proclamation made no mention of industry or new technology. Instead, it called for “a new guild of craftsmen, free of the divisive class pretensions that endeavoured to raise a prideful barrier between craftsmen and artists!” It aimed to break down barriers between art and different forms of craft. It dreamt of “a new building of the future that will unite every discipline”, which would “rise to heaven from the hands of a million workers as a crystal symbol of a new faith”. The front cover of the published version of the proclamation, drawn by the artist Lyonel Feininger, was a radiant image of a gothic cathedral.

Driven by the belief that a deep knowledge of technical skills was necessary for art to flourish, the Bauhaus taught metalworking, ceramics, textiles, photography, cabinetmaking, typography and theatre design as well as art and architecture. Its output included the mesmerising fabrics of Anni Albers, in which new materials such as cellophane are mixed with traditional threads, and the fantastical costume design of Oskar Schlemmer, which made people look like intergalactic dolls. Also the expressionist art of Wassily Kandinsky and the mysterious paintings of Paul Klee, both of whom taught there.

The early Bauhaus was sometimes more like a forerunner of the Californian communes of the 1960s than a laboratory for an industrial future. Johannes Itten, the shaven-headed Swiss artist who taught painting in the early years, was a follower of Mazdaznan, a pseudo-Zoroastrian fire cult that encouraged its adherents to purify themselves by, among other things, covering their bodies with tiny cuts. Old photographs show parties, dressing up and performances as much as technocratic endeavour.

One student would later recall rumours about the admissions procedure, whereby every applicant was allegedly locked in a dark room: “Thunder and lightning are let loose upon him to get him into a state of agitation. His being admitted depends on how well he describes his reactions.” Although these stories were “exaggerated”, they described the spirit that attracted the student to the school. When he arrived, in the aftermath of the first world war, he found a ragtag band of students and faculty “from all social classes”. Some were “still in uniform, some barefoot or in sandals, some with the long beards of artists or ascetics”.

It was too much for many residents of the Bauhaus’s conservative host city, for whom the weirdly dressed artistic types were subversive and possibly Bolshevik. “Men and women of Weimar!” read a newspaper announcement in 1920, inviting readers to a public demonstration, “our old and famous Art School is in danger!” The protesters didn’t stop it, although the Bauhaus moved to the industrial city of Dessau in 1925, where Gropius designed its famous building, and then briefly to Berlin, before it closed down under pressure from the Nazis in 1933.

Many leading Bauhauslers, including Gropius, Breuer and the school’s last director, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, emigrated to the United States, where they occupied influential academic posts. In 1938, the Museum of Modern Art in New York mounted an exhibition on the Bauhaus, with which Gropius was closely involved. Between them, Bauhaus architects determined the look of commercial and cultural America in the years after the war. The dominance of Gropius and Mies cemented the cool and rational version of the Bauhaus, which is its most distinctive – but not its only – contribution to the modern physical world.

Wherever Bauhaus ideas go, the objections of the burghers of Weimar have often followed. “Every child,” lamented Tom Wolfe in From Bauhaus to Our House of 1981, “goes to school in a building that looks like a duplicating-machine replacement-parts wholesale distribution warehouse”. Had there ever been another place on earth, he also said of Bauhaus-influenced America, “where so many people of wealth and power paid for and put up with so much architecture they detested?”

Now, though, on its 100th birthday it should be possible to see the Bauhaus not as a threat to civilisation, nor as the manifesto of a single vision of modern life, but as a place of abundant creative energy and technical skill. It has touched almost every aspect of cultural and commercial production, almost everywhere in the world. As these pages show, it means many things to many people.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion